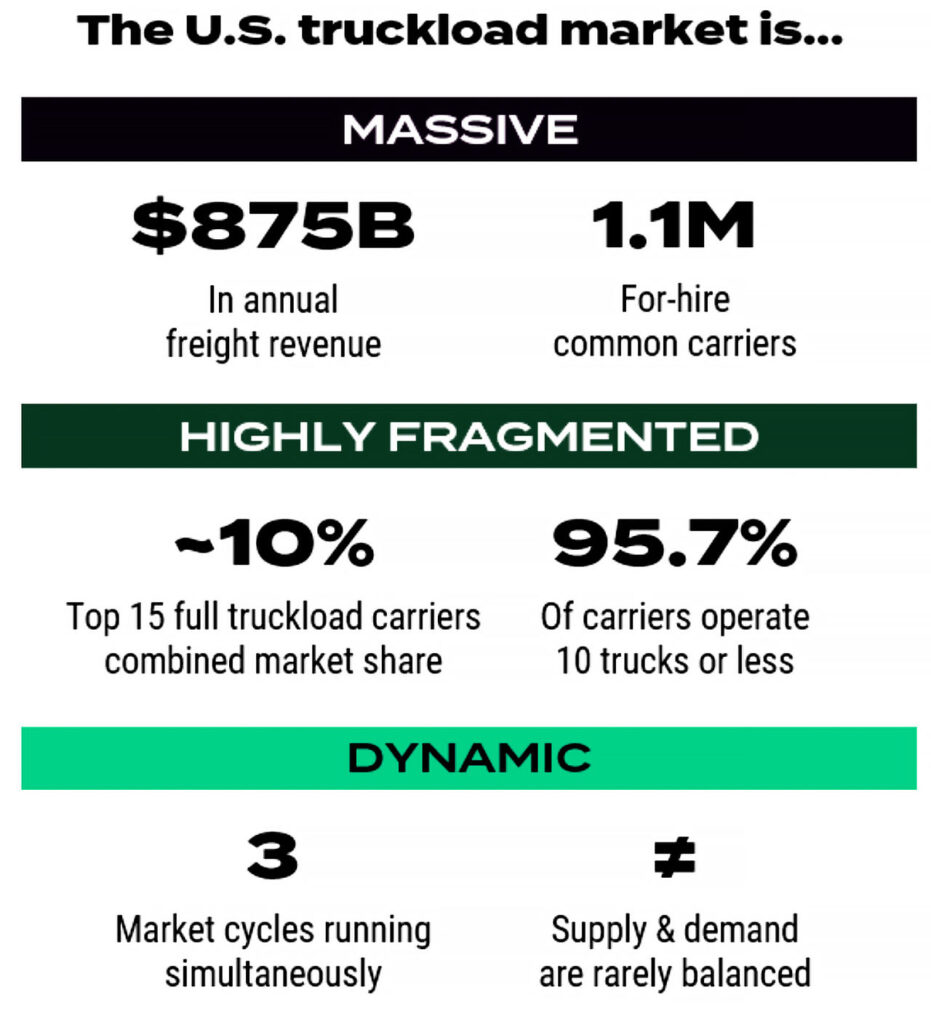

You can sum up the U.S. truckload market in three words:

- Massive.

- Fragmented.

- Dynamic.

Low barriers to entry (and exit), a limited regulatory environment and millions of market participants spending over $875B annually in gross freight revenues create a volatile environment where truckload rates and carrier capacity are rarely in a state of balance.

Supply & Demand Rule the Truckload Market

Between the constant volatility and a rapid influx of supply chain automation, the U.S. truckload market can be difficult to navigate.

Even though it may seem chaotic, the heart of the market beats to a consistent rhythm (and has for decades): the continual ebb and flow of supply and demand.

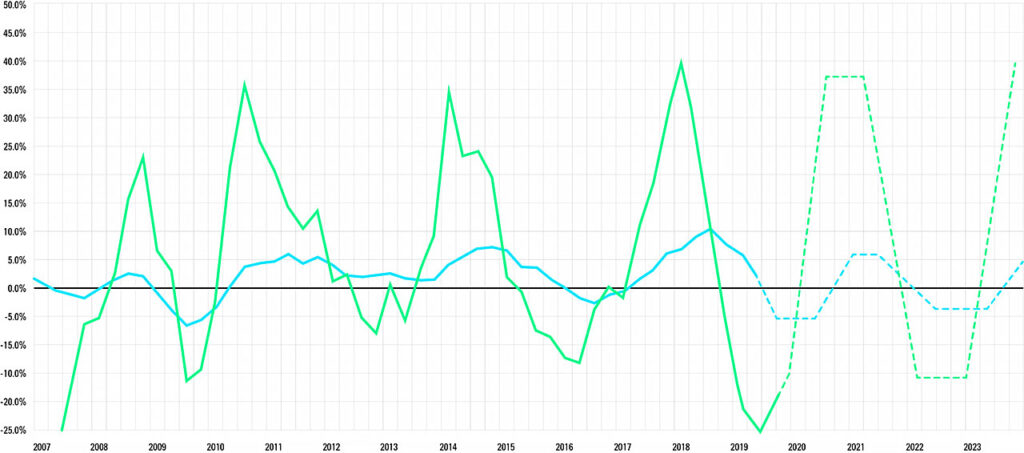

This re-balancing act creates a predictable pattern, and by measuring this pattern, we can clearly see a recurring cycle.

As long as the basic structure of the market remains the same (huge, fragmented carrier base), this cycle will continue to repeat with at least some level of consistency.

Knowing There’s A Pattern Is One Thing, Accurately Measuring It Is Another

Though this concept is simple enough, effectively cutting through the noise to measure this pattern is not.

You need a tremendous amount of data spanning several years, combined with insight to clearly map out the cycle.

We leveraged both to create the Curve, a tool for measuring the market capacity cycle.

Before we dive into the Curve, it’s important to understand the basic market structure and the forces that drive it.

Basic Structure of the U.S. Truckload Market

Supply (Truckload Carriers)

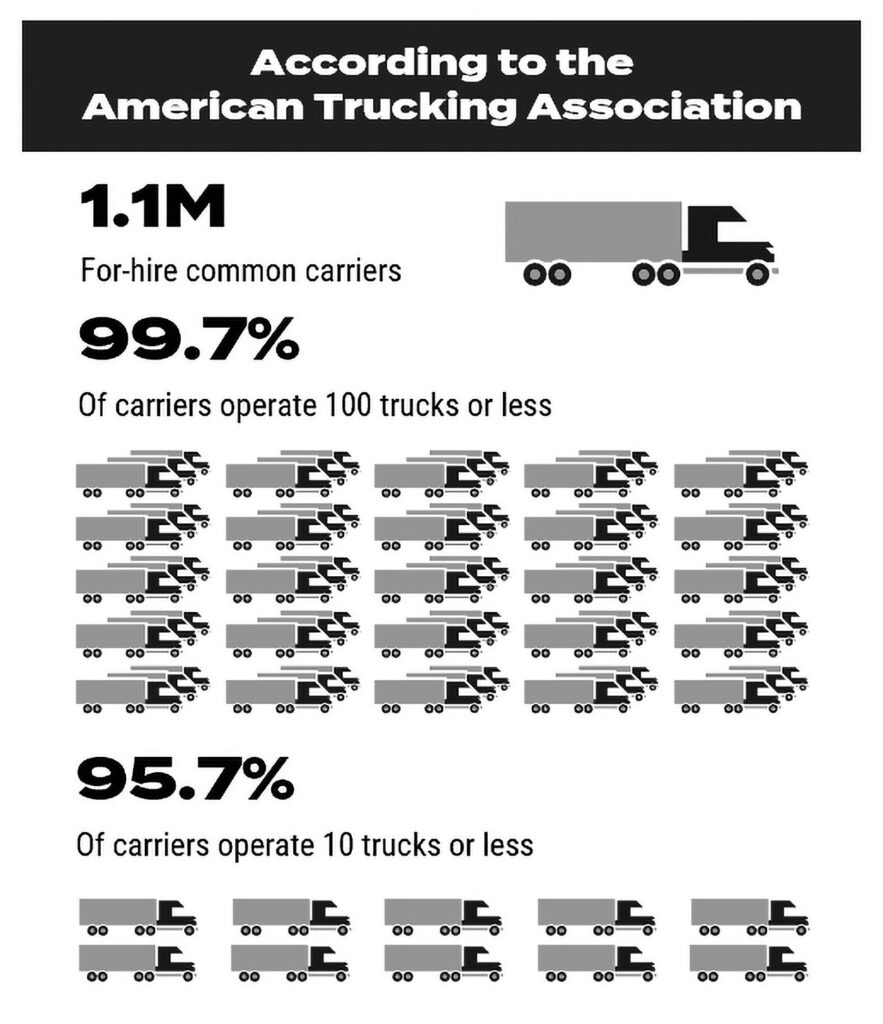

The U.S. truckload carrier base is huge (4.06 million Class 8 trucks in operation) — it is also extremely fragmented.

Though there are several large national carriers with +10,000-truck-fleets, no provider controls enough market share to dictate terms to shippers.

The top 15 full truckload-focused carriers only account for around 10% of total truckload market revenue.

In many ways, the hundreds of thousands of owner-operators, small, and medium-sized trucking companies dominate the supply base.

According to the American Trucking Association, there are over 1.1 million for-hire common carriers registered with the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration. 99.7% of those companies operate 100 or fewer trucks, and 95.7% operate less than 10 trucks.

Compare that to the U.S. parcel market, where two carriers (UPS and FedEx) combine for well over half of the total market share, or the rail industry, where seven Class I railroads control nearly 70% of all rail traffic.

The carrier base, both trucking companies and individual drivers, is also very fluid. When times are good, more capacity enters. When times are tough, capacity exits.

Though this dynamic is true in most industries, the rate and frequency it occurs in the truckload market is much faster than other transportation markets.

Why? Because the barriers to entry are very low.

It does not take a ton of training, time or money to get a commercial driver’s license, lease a truck and obtain an operating authority from the Department of Transportation.

If you wanted to, with a few thousand dollars (and a lot of dedication), you could have your own trucking company in just a few months’ time.

Again, let’s compare that to the parcel market: to build a competitive offering, it would take several massive sorting hubs, dozens of airplanes, thousands of trucks and vans, billions of dollars and probably a couple decades.

Or the rail industry, where most of your competitors were founded in the 1800s, are some of the largest real estate holders in North America and are highly regulated by federal governments.

In short, a huge, fragmented, fluid supply base = truckload market volatility.

Demand (Freight Shippers)

The U.S. shipper base (companies with physical goods to move) includes raw materials, finished consumer products, and everything in between.

This means the “demand” half of the equation is just as fragmented as the supply base.

There are hundreds of thousands of manufacturers, wholesalers, importers, exporters and retailers — each with its own agenda.

What to ship, how to ship, where to ship and how much to ship, is constantly changing to best meet the demands of each shipper’s customer base.

The barriers to entry (and exit) are also equally low. Any small business that starts shipping products is now in the market.

The “demand” half of the equation is just as fragmented as “supply”.

3 Cycles, 1 Complicated US Truckload Market

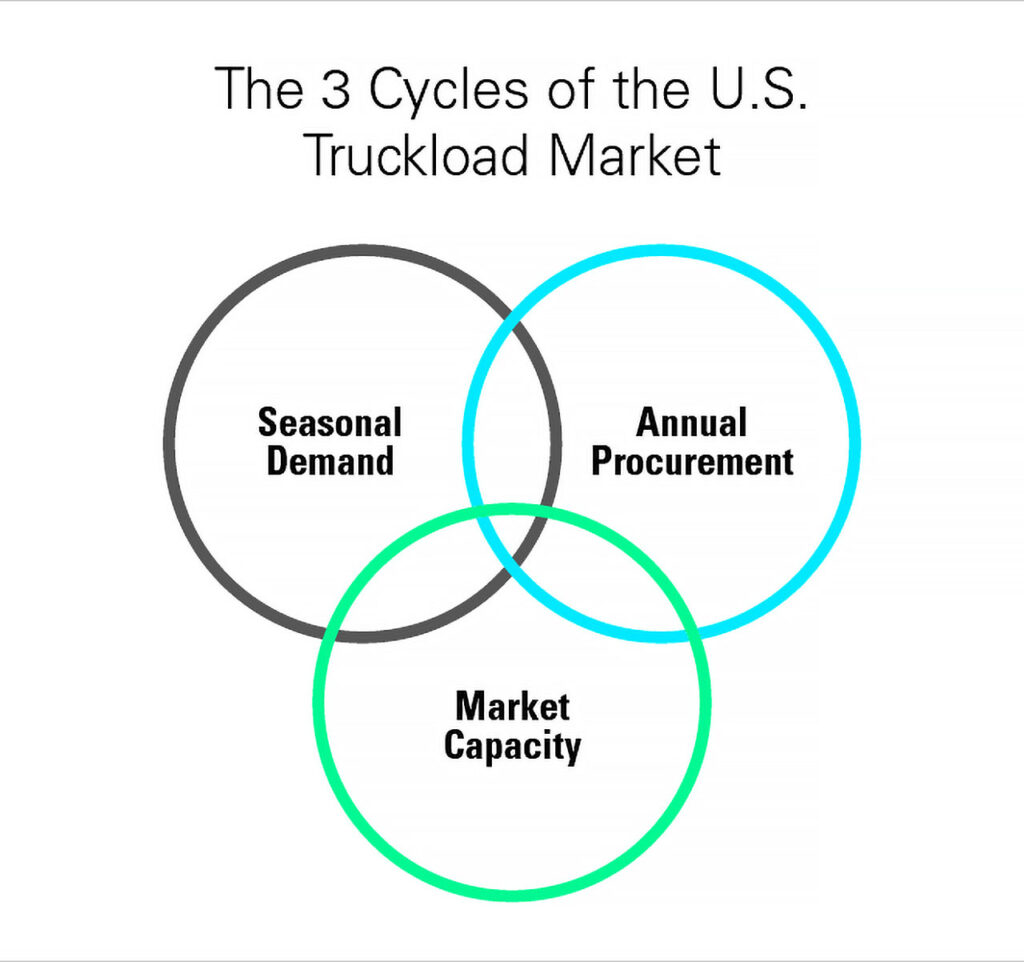

To add to the confusion of a massive, fragmented U.S. truckload market, there are three separate cycles operating simultaneously.

Two of them — the annual procurement and seasonal demand cycles — are well documented, easy to observe and relatively consistent.

The third cycle, the ‘elusive’ market capacity cycle, is harder to detect, but the key to understanding and properly navigating the market.

Cycle #1: Seasonal Demand

The first cycle refers to the fluctuating pockets of seasonal demand that occur with at least some level of regularity.

Many products and commodities do not follow steady shipping schedules throughout the year, instead surging over a relatively short period of time — generally a few weeks or months — in response to planned production or demand windows.

Examples include produce season, holidays, peak retail season, Christmas trees in the winter and barbecue products in the summer.

Trucks migrate to capitalize on the demand surge for as long as it lasts, then disperse across other market geographies once it’s over.

The seasonal demand cycle is perhaps the most stable cycle within the industry. Supply chains are designed to cope with these planned demand surges, and trucks are, in many ways, the ultimate form of mobile production.

With a prepared shipper base and a mobile carrier base, the market usually absorbs these seasonal fluctuations without major disruptions.

Some notable market events similar to seasonal demand are catastrophic weather events. These have a similar — though unanticipated — effect, creating relatively short-term, sometimes profound, disruptions in both supply and demand.

A few examples include 2017 hurricanes Harvey and Irma that battered the southeastern U.S. in rapid succession, causing unprecedented flooding in Houston, Texas and massive damage throughout the region.

The market’s ability to efficiently absorb these types of shocks is depends on the status of the third cycle (market capacity).

Cycle #2: Annual Procurement

Generally speaking, the industry consensus seems to be that freight rates will rise year after year. Assuming this, most high-volume shippers take their forecasted network out to bid in an effort to set annual ‘contract’ rates.

These contract rates are intended to hedge against spot market exposure, mitigate volatility and reduce financial risk. Most shippers confirm bid awards in Q4 and activate them in Q1 of the following year.

At a glance, it’s easy to assume that an annual procurement cycle would create consistency across the industry.

However, the shifting market dynamics shaped by three simultaneous cycles, combined with conflicting economic indicators and posturing from both sides for higher and lower rates, dampen any stabilizing effect.

Ultimately, the true success or failure of any shipper’s procurement strategy is at the mercy of the elusive third cycle, the one cycle to rule them all: the market capacity cycle.

Shifting market dynamics, 3 cycles, conflicting indicators and posturing from both sides dampen any stabilizing effect from ‘contract’ rates.

Cycle #3: Market Capacity

As heard from shippers in an inflationary market:

- ‘What’s going on in the market?’

- ‘How much worse is it going to get?’

- ‘What happened to my freight budget?’

- ‘How do I become a shipper of choice?’

These are common concerns for shippers during the inflationary leg of the capacity cycle.

Why? Because freight budgets were set during a period of deflation.

Shippers anticipated a future rate environment that never materialized and now their freight budgets and service metrics are paying the price (literally).

As heard from carriers in a deflationary market:

- ‘Where did all the loads go?’

- ‘Why are spot rates so low?’

- ‘Will I be able to keep all of my drivers loaded?’

- ‘How do I become a carrier of choice?’

These are common concerns for carriers during the deflationary leg of the capacity cycle.

Why? Because truck orders were made during a period of inflation.

Carriers anticipated a future rate environment that never materialized and now their fleet is paying the price.

As previously mentioned, the U.S. truckload market is massive and fragmented; no one participant can dictate terms and barriers to entry and exit are very low.

This creates fluctuating market pricing that floats on top of the ever-shifting balance of supply and demand. Those two forces are rarely in a state of equilibrium, and when they are, that period is brief.

When the market is attractive to carriers, current companies will order more trucks and prospective carriers will seek to enter. This process isn’t instantaneous.

At some future date (usually several months or quarters due to truck build cycles, order backlogs, driver recruitment and training, etc.) that additional capacity will enter the market.

As is often the case, the future market ends up being much different than the conditions that led carriers to make those business decisions in the first place. Trucking companies can overshoot, adding excess capacity which causes supply to exceed demand.

To put it another way, carriers bought high, now they have to sell low.

Tender acceptance begins to rise while rates begin to fall. Shippers press their advantage, driving rates as low as possible to cut costs after a couple years of blown budgets.

As rates start bottoming out, carriers pull capacity back out of the market, setting up the next inflationary leg, and so the cycle repeats.

What Is a Truckload Market Cycle?

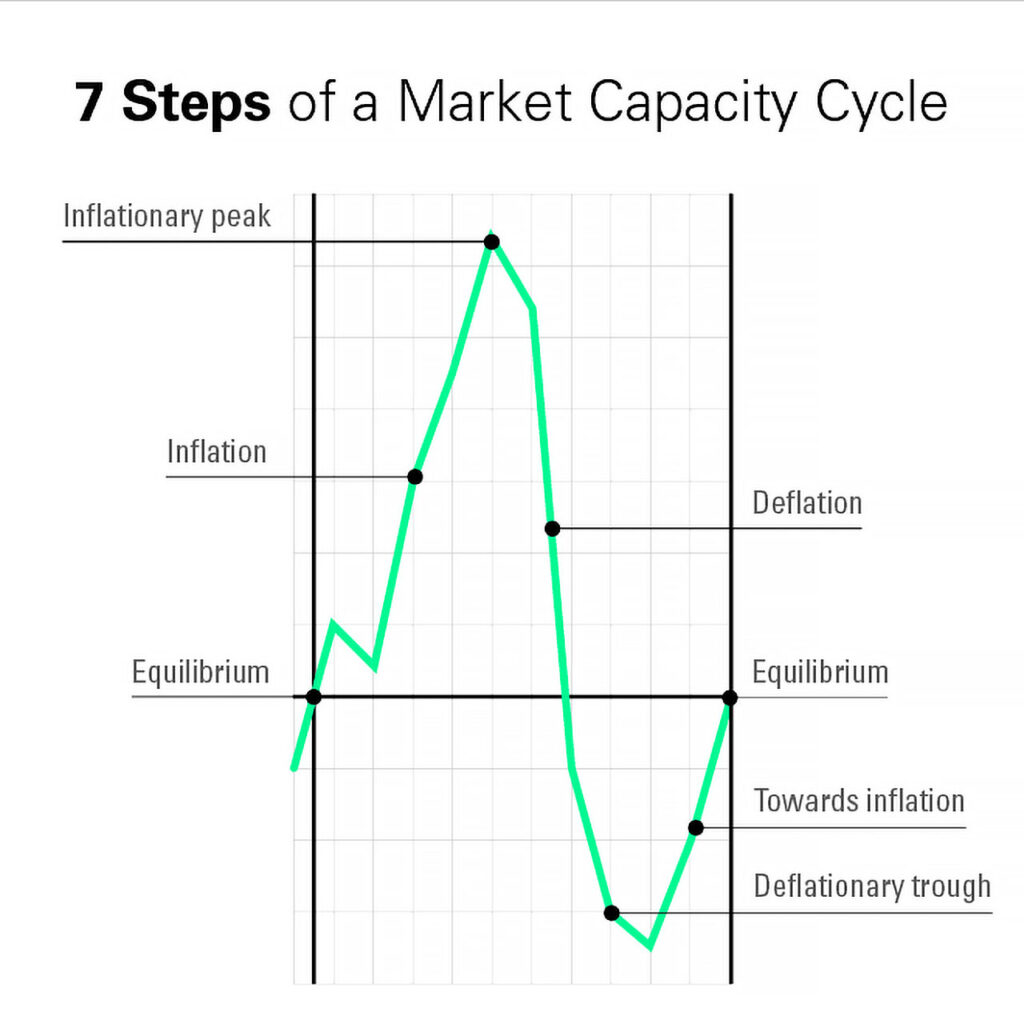

We’ve explained the basic market dynamics that drive the market cycle, let’s break one down, step-by-step.

- Market is at equilibrium:

Rates are stable, and capacity and demand are in balance. - Market begins to inflate:

There is less capacity than demand. Spot rates start rising and exceed contract rates as they reset to meet current market conditions. Capacity starts entering the market. - Inflationary peak:

Though primary tender acceptance rates are relatively low, and spot rates are high, enough capacity has flooded the market to pull the market downwards. - Market begins to deflate:

Spot rates start falling, while contract rates continue rising for a few more quarters, influenced by the recent peak. Eventually, as spot rates keep dropping and contract rates dip downwards, capacity will start to exit the market. - Deflationary trough:

Enough capacity has been pushed out of the market (relative to demand), and spot rates begin rising. - Market begins to inflate (again):

Though the wider market won’t realize it in real time, the upward climb begins, setting up the next cycle. - Market is back at equilibrium:

A new cycle begins.

Measuring the Market Capacity Cycle

Understanding truckload market dynamics is one thing — accurately measuring it is another.

We developed the Curve, our proprietary index based on thousands of daily loads spanning over a decade, to cut through the noise and measure the cycle.

It creates a simple, yet power visual that tracks the ebb and flow of capacity.